Ticketing queues are often the first point of interaction for visitors in a WHS, and as such, are often the main subject of visitors’ complaint. While waiting in line may never be fun, there are simple yet effective ways to optimize the design and operation of ticketing queues, so they don’t cause visitor dissatisfaction (and bad reviews).

First and foremost, the ticketing area where visitors wait must be comfortable. This usually means an indoor area that is kept clean, has fresh air flow, and is temperate throughout the year. If it is not possible to create an indoor ticketing area, then at the very least there should be protection from the elements (sun, rain, wind, etc.).

Secondly, ticketing stations must be clearly marked, with differing options for entrance fees clearly displayed, and if necessary in multiple languages. In general, the more information displayed, the more it helps visitors to prepare before reaching the ticketing agent, thus reducing ticketing times. On the other side of the booth, providing ticketing agents with the proper tools, such as workstations with fast internet and network connections for credits card processing and computer-related tasks, could make a huge difference in visitor wait times.

Thirdly, it is always a good idea to have self-serve ticketing kiosks with clearly displayed signage to indicate where they are. Often, electronic ticketing kiosks are put at separate entrances or hidden in corners, without appropriate signage to indicate what and where the kiosks are, thus leading to most visitors to miss out on this option. Naturally, keeping these kiosks are working and easy-to-use is of utmost importance as well. State-of-the art kiosk equipment with multilingual options could reduce ticketing lines especially on higher volume days, thus significantly increase visitor satisfaction.

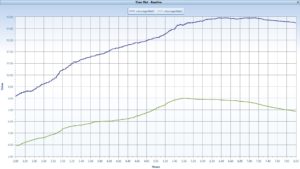

The final but most important “queue rule” is the importance of having a single ticketing queue rather than individual queues for each ticketing agent. The impact of these two types of line operations on the number of visitors served is seen below in the simulated models. The model displays three scenarios. Scenario 1, marked as “Multi-Queue,” simulates three ticketing windows, each with its own queue. Visitors approach the windows and choose any queue. When they reach the ticketing agent, it takes on the average 54 seconds, with a large variation from one visitor to the next, to obtain their tickets. Scenario 2, marked as “Single-Queue,” simulates the same three ticketing windows with the same average ticketing time of 54 seconds. The only difference is that the visitors in this scenario form a single queue. When the next ticketing agent becomes available, they walk to that particular window and buy their tickets.

Though it might seem counterintuitive, the single-queue design minimizes average visitor wait times. As can be seen from Figure 1 below, the difference between the two designs is very significant, i.e. approximately 14 minutes vs. 8 minutes for the Multi-Queue and Single-Queue scenarios, respectively.

Figure 1: Multi-Queue (blue) vs. Single-Queue (green) Results: Visitor wait times by time of day

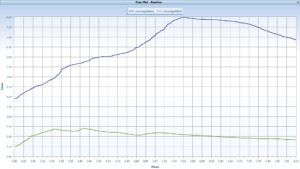

However, the advantage of the Single-Queue configuration can be lost if visitors are not immediately watching for the next available ticketing agent (and thus hold up the line) or there is a considerable distance between the front of the queue and the ticketing windows. By applying the Drum-Buffer-Rope concept explained previously, placing a waiting spot in front of each ticketing window maintains and further enhances the advantages of Single-Queue design. This particular design is shown above in the simulation model as Scenario 3, “Single-Queue with Buffer,” which simulates the same three ticketing windows with one difference: Visitors walk to the “buffer” located in front of each ticketing window when a space becomes available. The results shown in Figure 2 demonstrate that the average waiting time can be further reduced to approximately 2.5 minutes.

Figure 2: Single-Queue (blue) vs. Single-Queue with Buffer (green) Results: Visitor wait times by time of day

But how many ticketing windows is enough for your number of visitors? The answer should take into consideration not only visitor arrival rates and ticketing times but also the variability of ticketing times. As this variability increases, the efficiency per ticketing agent decreases. Visitors in a line with a large variability in ticketing times could experience long wait times compared to a similar line with more streamlined ticketing (or less variable ticketing times).

Unfortunately, variability is not a simple thing to control, as it is often affected by what we call “uncontrollable” factors, i.e. language difficulties, payment options, group size, etc. The good news is that there are controllable factors that can decrease variability, such as well-trained ticketing agents, reliable and fast connections to processing systems and well-informed visitors, all of which can be addressed using the solutions discussed above. Waiting in lines is never easy; making them is even harder. But with the right tools (i.e. correct modelling and simulations), creating lines with lower wait times and happier visitors is less guesswork and more science.

Stay up to date KCG’s blogs here and for insights on how to make visitor centers more efficient, check out our previous blog.

If you or anyone you know is interested in learning more about these techniques and how to implement them, please contact us via LinkedIn or our website.